The Baseball Hall of Fame will honor three Class of 2024 inductees — Adrián Beltré, Joe Mauer and Todd Helton received enough votes from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) to punch their tickets into Cooperstown. Jim Leyland, longtime manager of several teams, will join this impressive class of players on the dais, having been elected by the Hall’s contemporary baseball era committee, which examines the cases of managers, umpires, and executives whose greatest contributions came after 1980. These honorees will be officially introduced during a ceremony on July 21.

Those three on-field players have been deemed worthy of enshrinement by the 385 members of the BBWAA for their statistics, longevity, and periods of domination as being judged amongst the very best of their era (overall and at their position), post-season contributions … and, according to election rules, their “integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.” This last element of assessing the worthiness of admission to the Hall is referred to as “The Morals Clause.”

This begs the question, is baseball’s most esteemed institution a Hall of Fame or Hall of Morality?

This is a particularly thorny debate for baseball purists, significantly ramped up in intensity when assessing those who competed in what was deemed the “steroid era” in MLB. Unquestioned giants of the game, in any era of comparison, have been shut out of the Hall because a majority of voting writers have hypothesized that they used performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) to elevate their performance. Most notably not making the grade for enshrinement are Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Sammy Sosa, and Mark McGwire.

I believe that each of these individuals should have a plaque in the HOF. My logic follows.

Intoxicating Data, Ducats, and Delirium

Were these four ballplayers superstars? By any definition of the word, unquestionably yes.

Were these four ballplayers superstars? By any definition of the word, unquestionably yes.

Statistics? Inarguably, amongst the best cumulative and single seasons in baseball history and, in some cases, THE BEST in the game’s annuls.

By their singular presence on the field, each of these ballplayers shined a considerably brighter spotlight on the game. This outcome was 100% embraced by the Lords of Baseball, fans of the game, and even those who didn’t closely follow the sport. Uniquely, they each directly contributed to driving considerably more:

- Fans and non-fans to the ballparks — theirs and on the road.

- Viewers to their televisions and listeners to radio broadcasts.

- Advertisers and their mega-dollars to ballparks and broadcasts.

- Sales of baseball jerseys, paraphernalia, and accouterments.

- A massive infusion of revenue directly into the pockets of owners.

- Hometown pride to their respective team’s community.

- And, ironically, readers to baseball writers’ columns.

I believe that the 385 members of the BBWAA who cast ballots in the 2024 Hall of Fame election should have singularly evaluated players’ statistics and contributions to the game. What was their worth to the National Pastime during their era? During their career? How did they stack up on the field compared to benchmarks set by the acknowledged greatest to play the game? Did they have “HOF careers”?

Crossing into the Neverland of speculation introduces too many slippery slopes. I do not deny that there was a steroids era in baseball. To do so would be foolish. My point is that sneaking suspicions supported by hunches, observations, and even fair investigative reporting don’t go far enough to decisively cull the guilty from the group as a whole. Casting aside the issue of burden of proof — which is in and unto itself an alarming concept — BBWAA members do not have the capacity, let alone the moral authority, to conclusively draw a line in the sand and dictate, “Okay, you’re over there. You … you’re over here on this side.” Piazza, Bagwell — over here. Bonds, Clemens — over there.

To me, that has too much potential to cheat the history of the game.

Does one generally know when someone is of high moral makeup, possessing the intangibles of “integrity, sportsmanship, and character”? I would answer yes. You can see it. You can admire it. However, you can’t grade it with 100% certainty because we all have predispositions and biases.

What you can measure, evaluate, and even critique with focused, analytical rigor across this great game’s history is on-field performance.

The Choir Boys HOF

Does anyone have a moral compass that doesn’t waver? Methinks not. Were the Baseball Hall of Fame to admit only those associated with the game who showed a consistent and uncompromising adherence to strong moral and ethical principles and values, the number of plaques in the building could fit in a very, very small hall(way).

Does anyone have a moral compass that doesn’t waver? Methinks not. Were the Baseball Hall of Fame to admit only those associated with the game who showed a consistent and uncompromising adherence to strong moral and ethical principles and values, the number of plaques in the building could fit in a very, very small hall(way).

Unquestionably, some men stood tall not only on the field but in life. Jackie Robinson jumps to the front of the line, at least in my mind, in courage, outstanding achievements, and noble qualities. Roberto Clemente is also on this list.

As well, others put up exceptional numbers who also have a rep of being good eggs. Cal Ripken Jr., Tony Gwynn, Willie Stargell, and Brooks Robinson come to mind.

But Cooperstown is hardly the hall of charming, affable, good, or even in some cases likable men. It’s, as it should be, a club of men who were great at baseball.

The HOF is strewn with individuals — players, managers, owners, commissioners — with socially unacceptable flaws. I’ll insert the word purportedly on this list of portrayals of HOFers:

- Ty Cobb (violent and sociopathic racist)

- Babe Ruth (womanizer and heavy drinker)

- Grover Cleveland Alexander (alcoholic)

- Mickey Mantle (hard drinker)

- Cap Anson (instrumental in forging baseball’s color line)

- Kenesaw Mountain Landis, MLB’s first commissioner (made sure baseball’s color line would not be crossed)

- Tris Speaker (a member of the Ku Klux Klan)

- Tom Yawkey (owner with clear resistance to signing black players)

- Gaylord Perry (one of many players who walked the line of duplicitous behavior on the field to gain an advantage)

- Commissioner Bud Selig (turned a blind eye to rampant amphetamine use and the PED era)

Dark blemishes all. The contemptible behavior of some of these men categorically deserves society’s scorn and moral indignation. The measure of these individuals’ character is a stain that will forever be associated with them, and their actions debated and discussed by future generations.

History paints a detailed picture of how society worked and what individuals’ makeup was “back in the day.” History is who we are. Baseball’s history is captured in the museum that is the sport’s Hall of Fame. All of its history.

History paints a detailed picture of how society worked and what individuals’ makeup was “back in the day.” History is who we are. Baseball’s history is captured in the museum that is the sport’s Hall of Fame. All of its history.

In 2008, former baseball players’ union chief Marvin Miller, himself finally elected to the HOF in 2020, noted, “I think that by and large, the players, and certainly the ones I knew, are good people. But the Hall is full of villains.”

Moral qualities being recognized, if you accept my standard for admission — i.e., sterling on-field accomplishments — these superlative players all belong in the HOF. Regardless of how you assess these men and their actions and inactions, these ballplayers were Hall of Famers on the field.

I would be remiss if I didn’t address in this piece the lifelong bans of Pete Rose for betting on his own team’s games, and of the eight members of the 1919 White Sox after they threw the World Series. Confession: Rose, the game’s all-time hits leader, was my baseball hero when I was growing up. Like many of my generation, I admired his fire, his love of the game, his consistency. By all accounts, his era’s children felt the same about Shoeless Joe Jackson, one of those players banned for his part in the Black Sox Scandal.

These are transgressions of the highest order and go to the fabric of the game.

Still and all, I believe that both of these individuals should have plaques in the Hall of Fame. It’s not the Hall of Shame. It’s also clearly not a shrine to honor character. They are amongst the game’s greatest players, and their on-field achievements should be acknowledged. Because baseball’s #1 rule concerns betting on the game, Rose’s and Jackson’s plaques (perhaps segregated within their own room?) should note their offenses and the fact that their actions dishonored the game and that the stiffest of all possible penalties were dispensed. Let the Hall contribute tangibly to educating its visitors about these wrongdoings.

But what of the alleged PED offenders who rose to the very top of the game with scintillating, year-after-year, hold-your-breath on-field accomplishments? Those who kept us glued to our seats and brought unquestioned thrills and great value to the game as played in that era as a whole? Were Bonds and Clemons, for just two examples, putting up HOF numbers before suspicion of PED use surfaced in the game? If no one was definitively caught and proven to be using steroids, are they genuinely guilty of staining the game? What percentage of juiced hitters were facing juiced pitchers? Were Bonds and Clemons and the others under suspicion competing against rosters full of fellow users? How much did rampant use of amphetamines, commonly used for decades, ratchet up the game performance in the prior era? Like most substances in question in this debate, greenies weren’t even against baseball rules for long periods when they were allegedly used to speed recovery time from physical exertion and get “up” for the game. We’ll never know the answer to these questions.

How do you gauge the ungaugable? You don’t. Instead, when assessing the greatest, you compare performance. You juxtapose the most outstanding players’ numbers against their on-field competition, as well as era versus era. Stats, including modern-day analytics, don’t lie. They don’t need a judge and jury assessing “evidence” and character.

How do you gauge the ungaugable? You don’t. Instead, when assessing the greatest, you compare performance. You juxtapose the most outstanding players’ numbers against their on-field competition, as well as era versus era. Stats, including modern-day analytics, don’t lie. They don’t need a judge and jury assessing “evidence” and character.

So give them a pass? Hardly. Let generations — fans and non-fans — fuel the debate. That is how the past teaches future generations. History has always included the missteps, indiscretions, and lapses in judgment of any particular generation’s celebrated individuals. Great men and women who have made significant contributions have also made tremendous and sometimes grave mistakes. In baseball, as in life, let history paint the full picture of these athletes and men. It will not always be flattering. But it will always be worthy of a good, sometimes raucous, debate.

The statistically deserving of our greatest performers should be enshrined in the HOF. Once they are, they will have their morality or lack thereof scrutinized as any public figure who sets a bad example is remembered.

Legends aren’t saints. The purpose of Cooperstown is to house the history of the game, good and tainted. It’s inconceivable that the game’s hit king, its greatest home run hitter, and a seven-time Cy Young winner would not be worthy of admittance to the museum of the history of the game.

Their HOF Plaques

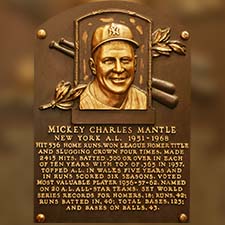

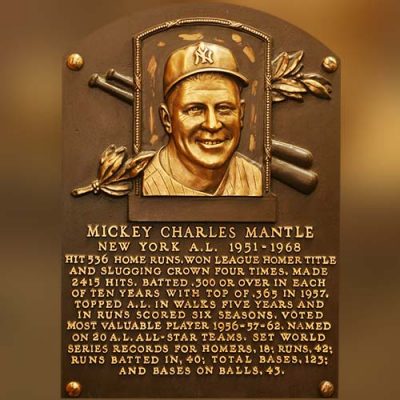

Photo Credit: Baseball Hall of Fame

When I visited Cooperstown and the Baseball Hall of Fame, I was awestruck. Indeed, the kid in the candy shop. I wish I could have spent days in this magnificent repository of the game’s history and shrine to its greatest players. I have zero doubts that when I return, I’ll get the same goosebumps.

I think back on standing in front of and reading Mickey Mantle’s HOF plaque. I saw him play in person only a few times when I was growing up, and those were the twilight years of his career. As I read his plaque, my mind leaped back to newsreels of this magnificent specimen of a ballplayer. Of his prodigious home runs from both sides of the plate. His speed. His enthusiasm for the game. His camaraderie with his Yankee teammates. His patrolling of center field. His World Series records.

I poured over his HOF plaque but honestly didn’t have to do so. Embedded in my mind were his three MVP awards and his 20 All-Star games. His Triple Crown year in 1956. His four home run titles. His shared quest with the great Roger Maris in 1961 for the single-season home run record.

I also knew many particulars about Mantle that were not articulated on his plaque. That he was never quite 100 percent for so many years. That his dad named him after future HOF catcher Mickey Cochrane, and taught him the game. That I was sad when his last year’s performance dropped his lifetime batting average below .300 (to .298). That he was the heir apparent to Joe DiMaggio, whose last season was Mickey’s first … as a 19-year-old Adonis.

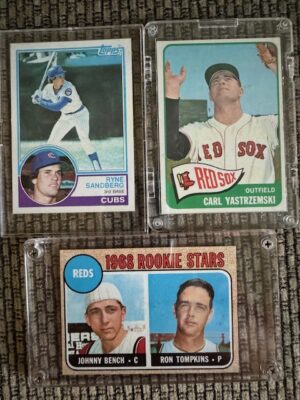

As I think back on that moment, I recognize now that The Mick’s HOF plaque was simply an extension of all of those baseball cards that I collected and studied as if my semester’s grade depended on it. Those Topps cards were de facto mini-plaques, presenting the facts that were his stats along with, on occasion, tidbits of the Commerce Comet’s life. I didn’t know it at the time when eagerly consuming the backs of those cards, but I know now that I was reading early versions of my hero’s HOF plaque.

Guess what was not on Mantle’s HOF plaque? There was no word about his self-destructive behavior — his hard-drinking lifestyle that eventually caught up with him and took him from us at the age of 63. There was nothing about my hero often failing to keep himself in game shape above and beyond the many legitimate injuries he suffered. Nothing about his after-hours activities; his carousing as, clearly, a high-functioning alcoholic.

It appears that those real-life characteristics and self-decisions were not what the baseball writers at the time included in their assessments of Mantle. They made him a first-ballot HOFer. Rightfully so.

It appears that those real-life characteristics and self-decisions were not what the baseball writers at the time included in their assessments of Mantle. They made him a first-ballot HOFer. Rightfully so.

The back of a player’s baseball card should be the sole admission ticket to stand with the game’s greatest players, all of whom were flawed in one manner or another. Call’em as you saw them. On the field.